RAJA-Danièle Marcovici Foundation at the Maison du Barreau de Paris to discuss the treatment of domestic violence in France

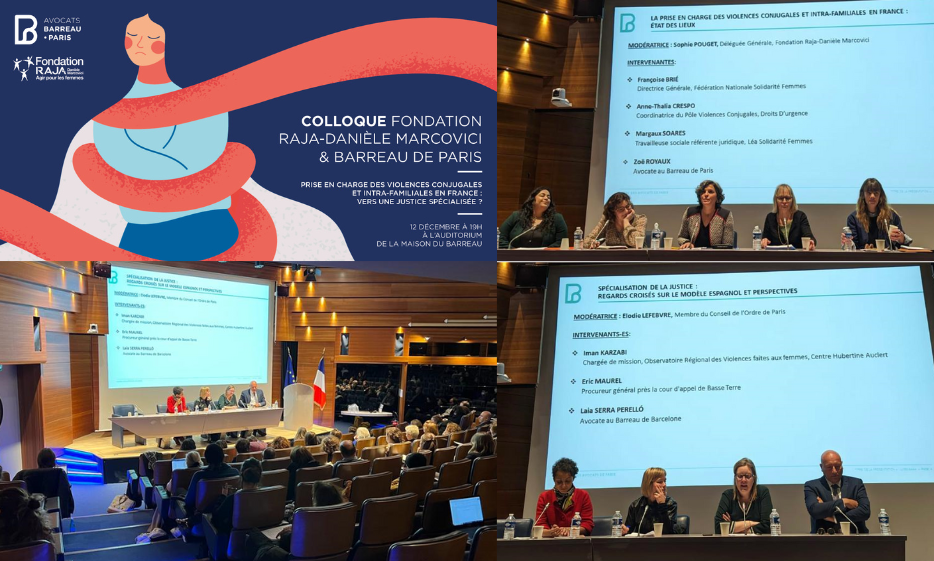

On 12 December, in partnership with the Paris Bar Association, the Fondation RAJA-Danièle Marcovici organised a symposium on the theme of 'The treatment of domestic violence in France: towards specialised justice'.

19 December 2022

Julie Couturier, Bâtonnière du Barreau de Paris, introduced the conference with a reminder of the extent of domestic violence in France:

- 122 women were killed by their spouse or ex-spouse in 2021,

- 186,000 people are victims of domestic violence

Faced with these alarming figures, Emilie Chandler, Member of Parliament for the first constituency of Val d’Oise, has been entrusted by the Minister of Justice, together with Dominique Vérien, Senator for Yonne, with a temporary mission on the judicial treatment of domestic violence. In order to help women go the “last mile” – to file a complaint to put an end to their ordeal -, not to forget the place of children – co-victims of violence -, and to address the issues of conjugality and parenthood, Emilie Chandler states the need to hear the voices of all those concerned by this phenomenon: those of the victims and of the judicial actors.

Treatment of marital and domestic violence in France: the current situation

Sophie Pouget, Executive Director of the RAJA-Danièle Marcovici Foundation, concurs with the observation of the Bâtonnière du Barreau de Paris and states the following data:

- 1 in 2 women declare that they have already suffered sexual violence

- 94,000 women are victims of rape every year, i.e. almost 1 woman every 7 minutes

- Calls to 3919, the national hotline for women victims of violence, doubled between 2021 and 2022

- Sexist and sexual violence, five years after the #Metoo movement, is constantly on the rise in France. While progressively more and more forms of violence are being highlighted and denounced – economic, institutional, political…-, victims do not receive sufficient support to ensure their protection and enable their reconstruction.

Françoise Brié, Director General of the FNSF, shares the data collected by the Federation during the year 2021 and emphasises the seriousness of the situation:

- Marital rape and death threats have increased by 47% compared to 2020

- Economic violence has increased by 25%.

- Out of nearly 100,000 complaints processed by the public prosecutor’s office, 40% are filed without follow-up

While Article 22 of the Istanbul Convention, signed and then ratified by France in 2014, sets out the obligation for States to take the measures “necessary to provide or arrange […] immediate, short- and long-term specialised support services to any victim who has been subjected to any act of violence”, the existence of specialised brigades, centres reserved for victims in hospitals, and courts dedicated to violence against women, is far from being a reality in France.

In order to take stock of the legal system and understand the specific nature of violence against women, Zoë Royaux, a lawyer at the Paris Bar, discusses the flaws in the French justice system:

- 1/3 of women killed by their spouse or ex-spouse had reported violence,

- Although since 2019, the serious danger telephone and the anti-seizure bracelet can be given to victims by the public prosecutor in order to ensure their protection, effective access to this device is very limited,

- The cases that do succeed are often dismissed and do little justice to the victims: on average, damages amount to 26,000 euros

The lawyer stresses the following aspect: “The complaint is a founding act: if it is not taken properly, the rest of the procedure is weakened. Family protection brigades have been introduced in the police stations of each department, hearing charts to assess the seriousness of the violence have been distributed to police staff and it is now impossible to file a report in the case of domestic violence since 2013. Nevertheless, there are some discrepancies with practice: poor dissemination of specialised tools, trivialisation of violence seen as simple “marital conflicts”, lack of measures to treat the perpetrators of violence, etc.

Anne-Thalia Crespo, coordinator and reference for domestic violence for Droits d’Urgence, shares the hell that victims of violence go through when they engage in legal proceedings: the perpetrator’s release from custody despite a criminal record that already includes a history of violence, the kidnapping of a child and a wife, the filing of multiple complaints, etc. Waiting times or the refusal of legal aid due to incomes that are deemed sufficiently high reveal the imperative need for the State to take responsibility for violence against women.

Margaux Soares, social worker and legal advisor for the association LEA Solidarités Femmes, reports other testimonies that condemn the powerlessness of institutions in the face of domestic violence: civil courts, criminal courts, child welfare… The system endangers and condemns the victims even more.

Specialisation of the judiciary: a cross-section of the Spanish model and perspectives

Iman Karzabi, project manager for the Centre Hubertine Auclert’s Regional Observatory on Violence against Women, reports on the conclusions of the 2020 study on the theme of “Policies to combat domestic violence: a cross-section of Spain and France”: 18 years after the promulgation of the framework law “Protection measure against domestic violence” establishing a specialised justice system and 5 years after the “State pact against gender violence” in Spain, feminicides have decreased by 25% and are 2 times lower than in France. The Iberian country also grants 6 times as many protection orders, 8 times as many serious danger phones and 4 times as many anti-seizure bracelets as its French neighbour.

Laia Serra Perelló, a criminal lawyer at the Barcelona Bar Association, stresses that these advances have been made possible by a ‘social consensus in favour of differentiating domestic violence from violence against women’. A nuance is nevertheless brought to the success of the national measures: many of the actions foreseen by the 2004 law have not been implemented, the parental alienation syndrome prevails and condemns the children to be exposed to the violent parent…

In order to put Spain’s specialised justice system into perspective with the situation in France, Eric Maurel, public prosecutor of the Basse Terre Court of Appeal, mentioned the shortcomings of the French justice system which prevent the improvement of the treatment of domestic violence: Under-staffing of magistrates, court clerks, few courtrooms and training for police and lawyers, budgetary insufficiency… At the same time, he stresses the capacity of the courts to evolve rapidly in the face of the demands of civil society and sees digitisation as a means of making legal decisions more fluid.

Conclusion

Dominique Verien, Senator for the Yonne, Vice-Chairwoman of the Delegation for Women’s Rights and Equal Opportunities for Men and Women and temporary representative to the Minister of Justice on the treatment of domestic violence, concluded the conference by stressing the following points of attention that need to be put in place in France:

- Allocate a budget to a specialised justice system for this type of violence,

- Train all the actors of justice involved in the procedures,

- Reduce waiting times,

- Make legal decisions transparent to facilitate the reconstruction of victims.